The Last Forgeron

Who created the wonderfully detailed iron balconies in New Orleans? In 1920, the last in a line of French Quarter forgerons put down his hammer. M. Charles Antoine Mangin, Jr., a Creole and fifth-generation iron monger, decided to retire because he could no longer find workers interested in learning this art.

Each piece that came from his shop was unique and original. On June 6 that year, Times Picayune reporter Marguerite Samuels published an interview with Mangin in which the smithy explained his ideas of the French Quarter’s iron works.1 Cast iron works are create from molten iron cast into molds. But each wrought iron work is unique.

Wrought iron is like an oil painting – every stroke is put on by hand, and there is only one copy in the world. Cast iron is like printing – once you have the plate, you may run off millions of copies.

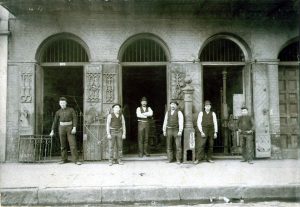

Mangin was born in New Orleans on August 17, 1854, but his grandfather arrived from France in 1832 and set up the shop at 621 Bourbon Street; there was a forge in the courtyard of that address at least until Mangin’s retirement eighty-eight years later.

I hardly had to learn at all. It was born in me. I have worked around a forge since I was fourteen. Every member of my family has been an ornamental ironworker, except one, the smartest – he was a priest.

This brawny and mustachioed forgeron lived above the shop with his French-born wife, Antonia Meraux Mangin. Over the years, various close relatives lived with them, including Charles’ brother John, who also worked in the shop.2 But at the time of his retirement, Mangin was sixty-six years old, and the couple were living alone with no children to carry on the legacy.3

Mangin was said to know more about ornamental ironwork than anyone else, and he made this clear as he led the reporter on a tour of the Vieux Carré. The wrought iron at 621 Bourbon was among the most detailed in the French Quarter, and each piece was made by hand in the forge at this address. Mangin also loved the French-made balcony next door at 619 Bourbon, and believed it to be the oldest in the city.

But he considered the works gracing the façade of Waldhorn’s Antiques Shop at 343 Royal Street to be the most beautiful.

It has the French brass ball at the end of a scroll-design which could not have been made in less than eight heats for every scroll. And the scroll is repeated an uncountable number of times.

Although etymologists would disagree with him, Mangin claimed to know the origin of the word veranda:

A certain Hidalgo of Spain, by the name of La Veranda, with an open gallery outside his house, had a sudden architectural inspiration to protect his family against sun and rain. He ran up pilasters, and put on a roof – and behold! the snuggest balcony Seville had ever seen. Delighted, his daughter never left the spot. She was a striking beauty, with Castilian coloring and a lift to her head that made passersby say, “Look! That’s La Veranda.”

After closing the shop, Mangin continued working with iron, but on a smaller scale: he became a locksmith.4 He died in 1924 and is buried in St. Louis Cemetery Number 1. Antonia passed away just seven years later.

1 Marguerite Samuels, “Art in the Iron Verandas of New Orleans,” Times Picayune, sec. 3, p. 1, June 6, 1920. Quotes in this blog post are taken from this article.

2 Twelfth Census of the United States, New Orleans City, June 9, 1900. Thirteenth Census of the United States, New Orleans City, April 22, 1910.

3 Succession of Charles A. Mangin, Civil District Court, Parish of Orleans, State of Louisiana, No. 153281, Div. C, Docket 1, June 26, 1924.

4 Soards’ New Orleans City Directory (New Orleans: Soards, 1923), 1735.

Ironwork image: By aprilzosia (Flickr: 4.5.08) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons